Homenajes

Homenajes

Photo by Ray Santisteban

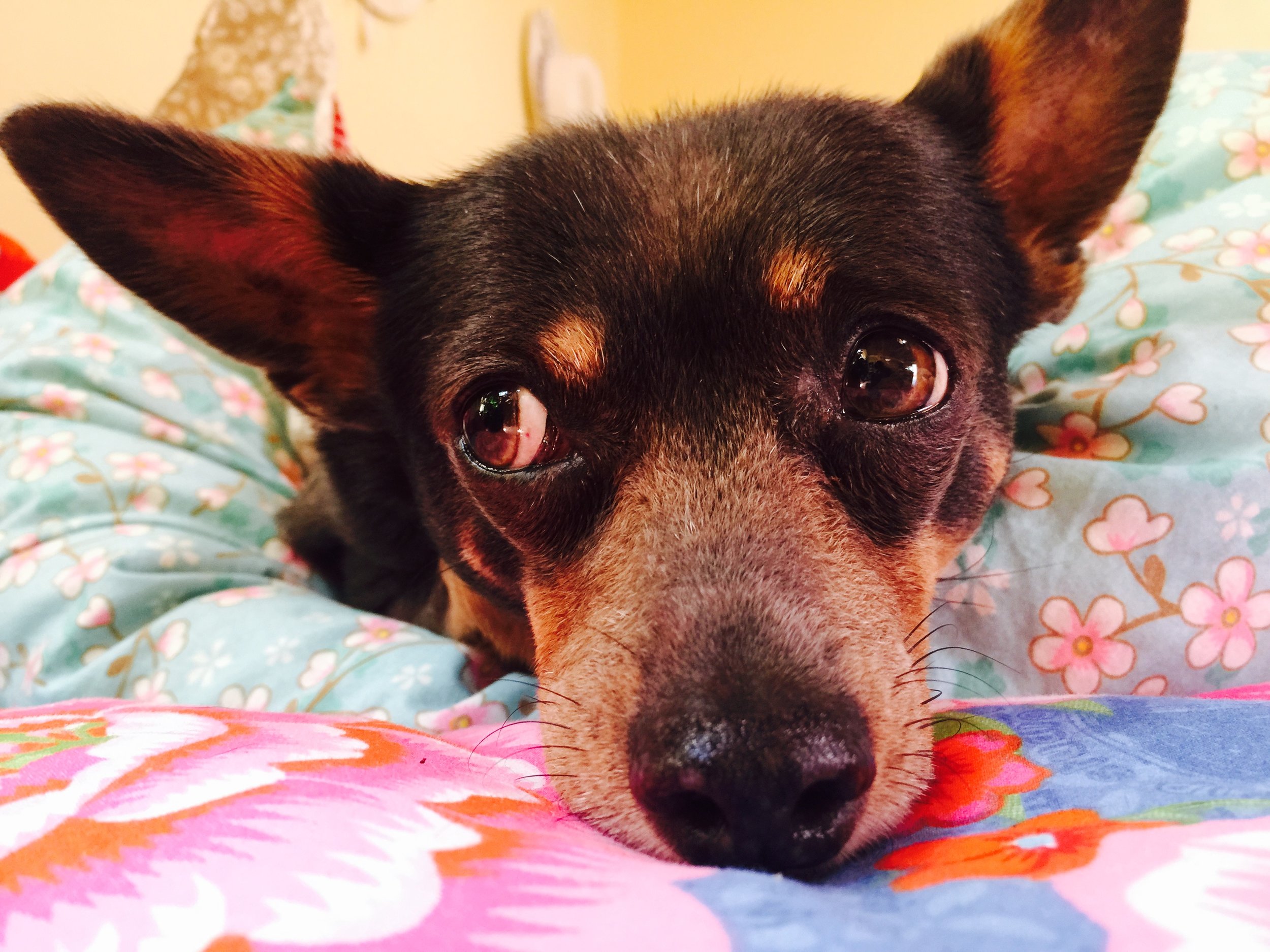

Barney Fife

(dropped off before dawn, Labor Day, 2007, picked up April 30th, 2017, before midnight)

He arrived with giraffe legs and goldfish eyes in a body so malnourished I considered naming him “Gandhi.” But after a day it was clear he was a double for the cowardly deputy of “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Barnitos was abandoned in the pre-dawn darkness of a Labor Day weekend, 2007. Someone of wide girth leaned over my scalloped wire fence, deposited him, and rushed off into the anonymity of night leaving only the swagged fence as evidence.

My resident canine pack was whipped into a frothy fury. Who could sleep? I went to investigate, opened the front door, and was horrified to see a tlacuache on my front porch. After slamming the door, I re-opened it a crack, and realized my mistake. When I knelt down, Barney climbed onto my lap and into my life.

He was more pasha than puppy. Barney was used to being carried about and fed by hand.

It seemed to me a dog this babied had to have an owner somewhere crying her eyes out, even though the bent fence said it all. Maybe Barney had been abducted, and to put this idea to rest, I contacted an animal intuitive.

The animal intuitive told me Barney had lived with a large “Hispanic family” (her words, not mine), and that a little girl had been his caretaker. I think she must’ve fed him Fruit Loops because he was never a big eater and nibbled his food indifferently like a Texas debutante. The intuitive also said Barney’s original owners had threatened to give him away if the child didn’t take better care of him. And true to their threat, they did. (What did they expect? She was just a kid. No wonder Barney arrived with dirty ears and no appetite.) And so, owners number one gave him way to adult relatives. But soon enough, the intuitive continued, this family got tired of chasing Barney down the street, because he’d cannon-ball to freedom the moment they opened the door. This was certainly true; he did this at my house too, but luckily we had a fenced yard.

That is why Owners Number Two decided to drop him off at a nice house with a big yard on a weekend when they were no doubt headed out of town. I tried to find Barney a home better than mine, but whether it was my own ego or circumstance, he stayed, and Ray and I became Owners Number Three.

Barney was happiest when slung over someone’s shoulder like a wet towel. Are we all so obviously needy, so readily vulnerable and easily detected? It broke your heart to see this.

Otherwise, he was one mean dog, cussing in canine language to every living being that came near him, complaining night and day about his sad fate having to share his home with a parrot, three cats, and too many dogs to count.

His hobby was chasing after the cats, and this habit, from which he could not be broken, no matter a million scoldings, forced the cats to live in the office with their own corridor to outdoor safety. He got his karma though when at a closing ceremony for my move to Mexico, he burned his butt when he sat on a lit candle.

Ray Santisteban, Barney’s “father,” had this to say: “Barney always wanted to be a chief. But it was not meant to be. Poor little Barnes.”

Pobre Barney indeed. He trotted about with his shoulders hunched like a vampire, ready to tell anyone off, quick to break into fights. Once he even got into a violent scrap with one of the other dogs, (Chamaco), and left his rival with a limp for life. Well, Barney was one mean little dude.

Until he met true love.

“Is this the same dog?” everyone asked.

Yes, love has a way of making changos of us all, whether we like it or not. And so, Owner Number Four came into Barney’s life. Writer Macarena Hernández first greeted Barney in the language he understood; baby talk. ¿Como estás, mi chiquitito? I knew at that moment Barney had found true love.

Macarena couldn’t understand why Barney would always piss on her truck’s tire when she came to visit. I had to explain, “Maca, don’t you get it? He’s claiming you as his!” Personally, I think she liked this.

When I moved to Mexico, Maca house-sat my home and dogs. Finally, when I decided to stay in Mexico and was forced to part with some of my pack, it was clear to me Barney and Maca were meant for one another, even though she had severe dog allergies. Love does not come without pain.

Maca had this to say about life with Barney: “It was great to see his second act. It reminded me that change is possible. He was such a jerk when he was around other dogs, but it was because les tenia miedo, he was afraid of them. Deep down inside, I knew he had a soft spot. He was more comfortable around people than his own kind.

Barney wanted to be an only dog. And I could relate, as one of eight kids who fantasized about getting adopted by childless strangers, I spent my childhood dreaming of a house where I wouldn't have to share the bathroom, bedroom, or love with so many others.

Everyone knew Barney. He went to school with me and traveled all over Texas. The passenger seat of my truck was his favorite place. My friends and students all loved him. He was hip and popular. I was surprised that no one here questioned that he was the coolest little dude. Even his old vet said he was like a different dog.

Barney waited till I arrived back to Texas on a visit, and then decided it was his time. He became ill for 48 hours with a mysterious condition that baffled the vets. I was there to help Macarena when there was no other choice but to put him down.

After the vet gave Barney the injection and he had crossed over, Macarena noted Barney looked younger than ever.

I too noticed something. All at once there was a bubbly energy bouncing around that dreary room, a fountain of infinite joy, a playfulness that made me laugh out loud. Then I knew.

It was Barney.

María Luisa Camacho de López.

Photo courtesy of Kathy Sosa.

María Luisa Camacho de López: Maestra, Madre Espiritual, Mujer de Luz, Keeper of the Community’s History

(June 21st, 1935 – September 4th, 2017)

“¿Quién es esa mujer?”

When Señora López entered a room, everyone noticed. It was not just the way she dressed, which was like no one else—in stunning Mexican garments of indigenous origin—but the way she wore these textiles, as radiant and graceful as a nopal in full bloom, as glorious as a queen.

Even her name was elegante—María Luisa Camacho de López. The name of una marquesa or duquesa perhaps. But she was, lucky for us, a woman of our time, una mujer as powerful as Paricutín, the little volcano that erupted overnight in a farmer’s cornfield.

In another age, María Luisa Camacho de López might’ve been an ethnographer, an anthropologist, a curator. In her lifetime she was known simply as la Señora López, wife to Eddie Lopez Jr., mamá to her three kids. Their vibrant house on the West side behind the HEB became an informal cultural center, a community oasis, a place of the spirit where everyone was welcome no matter who you were or where you came from. In the true tradition of a person with spiritual gifts, she shared her knowledge with anyone who asked, without judgement, without expecting anything in return.

Pásale, come on in. Professors and politicians, students and neighbors, artists and journalists, everyone dropped by. And everyone was nourished with food, music, color, stories. In her house you laughed a lot.

Daughter Rose added this: “During the holidays my mother and dad would make all kinds of tamales to give to everyone they knew, and sometimes, even to complete strangers. Along with tamales they served buñuelos. On Christmas Eve, there was as well pozole, champurrado, ponche navideño and rompope. Our house was open to everyone to come watch the baby Jesus being placed in the nacimiento manger at midnight. Whomever my mother gave the honor of putting the baby Jesus a dormir, became her comadrita.”

Artists across town thought she was cool and came away changed by what la Señora López shared. Women who wanted to dress like her, learned from her lips the history of the textiles they admired. Neighbors who needed a novena, looked to la Señora López to lead them in prayer. Whenever anyone had a question about a Mexican custom that someone had forgotten or never been taught, as teacher and guide la maestra López was there.

Word spread. You have to meet this amazing woman on the West side. She was a walking museum of Mexican culture, especially textiles. Without realizing it, she was nourishing Texas with the history that was rightfully theirs but was not taught in the schools, even though the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had promised to preserve their Mexican language and culture. When the Alamo was remembered, the legacy of the people’s Mexican heritage was forgotten. Señora López was sent to San Antonio to keep the community from forgetting who they truly were.

Born in Guadalajara, to a rural teacher, Señora López traveled with her mother as a child from pueblito to rancherías throughout the states of Jalisco and Michoacán. When a generous little girl from Paracho gifted her with un huanengo, a Michoacan blouse, her love of textiles began.

Daughter of un rebozero, a maker of Mexican shawls, Señora López was descended from a family of tequileros from Los Altos de Jalisco, where she inherited her love of charreria, and was twice crowned queen.

One day as a young woman in Guadalajara she is having trouble raising the metal curtain to the shop where she works. A polite young Tejano on vacation helps her. Neither of them realizes at that moment, the curtain to the next chapter of their lives is being raised. Through a courtship of letters from San Antonio to Guadalajara, their romance begins.

Here’s the black and white photo of Mr. and Mrs. Eddie Lopez’s wedding. September 12, 1958. How handsome and young they both look, la Señora López like a Churubusco movie star. Did you know her satin wedding gown with its fifty-six buttons down the back was hand-sewn by a Guadalajara convent? ¡No me digas! ¿Es verdad a nun went blind from the labor? Solo Dios sabe.

In the itacate of her heart, Señora Lopez brings to Texas her knowledge and love of everything Mexican, including her favorite recipes—pozole estilo Tapatio and carne en su jugo. And her favorite dichos—Ven la tempestad y no se hincan.

If you walked past the little house on Park Avenue behind the HEB and heard Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” pouring out the windows, that meant la Señora López was reading a book. Or if the house was throbbing to the sounds of los Huapangos de Moncayo, Guadalajara, or sones huastecos, or jarochos, she was housecleaning. If her three children were at home, they joined her in belting out Cri Cri’s “La Patita” or “El Ratón Vaquero.” She adored "Dos palomas al volar" as sung by Antonio Aguilar. But as a true daughter of Guadalajara, she loved best mariachi music, especially “A que manera te olvido.”

Where in the little house on Park Avenue did Señora López store so many treasures? Textiles and folk art she and her husband collected were bought with a salary earned at Kelly Air Force Base, where Mr. López worked as a mechanic. They were no Rockefellers, but their collection ferried back to Texas by hand on the bus from Mexico was stunning, created with love and care from a couple who knew what they liked and knew what was lovely.

On their vacations south, Señora López would often run after someone who was wearing an especially unusual bag or belt to ask if she was willing to sell it, or if there was anyone she knew willing to sell an old item. This was how she managed to capture an array of textiles that spanned from the 1920’s to the sixties.

All across Texas, Señora López gave lectures. It didn’t matter who you were, she was not judgmental, but open to all who wanted to learn and know, so that everyone could love and know Mexico as she did.

As she grew older, Señora López taught us how to age with pizazz. She never graced the cover of Texas Monthly, but she was a style icon in her striking Mexican huipiles, with her hair pulled back in a chongo, flowers and ribbons adorning her radiant face. Tenia su propia luz. She had her own light.

“You look beautiful today, Señora.”

“Uds. me ven con ojos de amor,” she would say modestly.

On August 15th, 2008, Señora López lost her husband of almost fifty years and spent many of her widowed years bound to her bed due to ill health. “Muy pronto voy a caminar otra vez,” she would say, optimistic as ever, convinced good health was just around the corner.

During these years, Señora López may have lost her memory for what happened at breakfast, but long ago was as clear as the Jalisco blue skies of her childhood, with stories summoned up from storage with precise dates and details.

It was her appreciation for life that made her life rich.

Twice Señora López became so ill she was close to death. Twice her family expected her to cross over, and twice she recovered. When she fell ill the third time, her family said “We all thought our gatita with nine lives would bounce back, but this time she was tired and surprised us.”

She crossed gently in the presence of her three children and their queridos. Rose Marie and partner Liza Zarate, Eddie III and wife Veronica, Ralph and his partner Sylvia Sepulveda Gomez, three sisters Guillermina, Graciela and Esther, many nieces and nephews and countless friends from all corners of the world made peace with her departure—“She’s no longer suffering, she’s back in the arms of her amor eterno.”

For a time, Señora Lopez had a textile museum on the famous River Walk, but that was long ago before the rents went up. Perhaps this was why Señora López dreamed that someday a major museum would buy her personal collection of rebozos, her 1920’s China Poblanas, and velvet tehuana outfits, but little by little, financial circumstances forced her to sell her treasures, piece by piece to collectors. Today a good part of the María Luisa Camacho de López textile collection is now housed and cherished by the National Museum of Mexican Art of Chicago where her light continues to iluminar.

September 7, 2017

Casa Coatlicue

San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato

Mexico

Sandra Cisneros

Chamaco: A Remembrance

(d. June 14th, 2016)

I don’t know how old Chamaco was when he first came to me May of 2006. I’d already had Peanut, a black mutt, dropped into my life a few months earlier in February, and Chihuahua Barney would follow a few months later in September. All three dogs were drop-bys the year before my mother would die, as if the Universe was saying, “Get ready.” Their love would keep me from drowning when my heart was cracked wider than I could bear.

Chamaco was singular for being disposed of from the window of a moving car by a jealous rival. An animal intuitive told me Chamaco had lived happily with a young woman before me, but a small man, who couldn’t stand sharing his woman with a dog, entered the woman’s life, and Chamaco was kicked out of this love triangle.

I suspect the story is true. Chamaco knew how to toss the bedcovers with his snout and let himself under. His nails were perfectly groomed. And to top it all, he came with an annoying insistence to French kiss, which I put a stop to at once.

My then-neighbor, Dave the Cowboy, plucked homeless Chamaco off our street and introduced us in the driveway between our houses.

“I found a Chihuahua,” Dave said proudly as if he’d bagged him himself. He was carrying his prey with outstretched arms as if he was afraid of catching ticks.

“Give him here!” I scolded. The poor creature was trembling. “What’s his name?”

“Little Dude.”

Little Dude, I thought, Too goofy.

“He keeps escaping through the bars of the fence, so I keep him inside.”

“I’ll keep him for you till you find him a home,” I said. But I already knew he’d found his true home when I held the dog tightly. He was as warm as a stone sitting in the sun and radiated a vibrant, intelligent energy.

I looked into the dog’s amber eyes and told him, “You will never be afraid again.” The dog met my eyes and answered, “I believe you.”

Almost immediately I named him “Chamaco,” which funny enough, translates more or less as “Little Dude,” but doesn’t sound as goofy in Spanish, I swear. Its more precise translation is “kid.” Chamaco was every bit a Chamaco, a brilliant spark from a bigger, eternal conflagration.

Even then I remember el Chamaquín as a handsome creature with eyes a deep, flaming amber and a coat the two-toned black and tan of a Doberman’s. He was too big to be a true Chihuahua, I thought, and luckily had not inherited the Bette Davis eyes of that breed. Instead, he had the intelligent gaze of a black panther. And though he was only as tall as the top of my boot, he was commanding, with perfect proportions and a brave demeanor.

I’m sure Chamaco had some Xoloitzcuintli, Mexican hairless, in his ancestry, because of bald spots on his back. What hair he did have was coarse, except for snout and legs, and some of it stood straight up like a metal broom. Exceptional of hearing, he was recklessly courageous, and often the first of my pack to sound the alarm.

Chamaco was as serious as Buster Keaton and rarely laughed. He barked only when he meant it, a sudden train of rising sounds surprisingly high-pitched that ended with his snout and tail trembling in high alert.

A serious accident cleft Chamaco’s life in two. He suffered a bad limp from a dog fight with Barney, his rival. The fight left him crippled for a day with a twisted spine. He survived with one lame leg, which he managed to hitch along like an afterthought when he walked.

Hard to believe he’d once been as frisky as a flea, leaping amazing Baryshnokovian heights, scampering at full speed to run away from home to play with his dog buddy Napoleon and steal cat food set out by neighbors for the strays. He’d sneak back remorseless and wait at the front gate quietly for someone to notice and let him in, as if the spanking he’d get was worth it.

Chamaco was smart alright. Smarter than a dog and smarter than a human too. He looked at me with a gaze so intense it smoldered. I’m crazy about you, he seemed to say. I never had a dog who looked at me like that. Come to think of it, I never had a human who did either. He loved the way Pepe le Pew loved the cat.

When I decided to move to Mexico in 2013, some unwise wise woman told me I needed to give up all my pets. Reluctantly I did a Sophie’s Choice, but some pets boomeranged back to me. The wise woman was wrong. Eventually I gave her up instead.

But before I knew to listen to my own intuition, Chamaco was packed off to live with Macondista Erasmo and his partner Pajarito in New York City. In photos Erasmo sent, Chamaco looked hip in his new Manhatten digs, went for long walks, gave up table scraps and was, as a result, bien buff. He was living the life I couldn’t give him, I reasoned and sighed.

Then, almost as if I’d wished too hard, he returned to me when Erasmo had health issues. After a long plane ride from D.C. to Houston to Mexico, Chamaco joined me and his Texas dog colleagues, Peanut and Dante in San Miguel, and met new Chihuahua rivals, team Ozvaldo and Luz.

He adapted to Mexico quicker than I did, buoyant as the Guanajuato clouds, as natural as if he’d been born here. He’d watch me closely every morning and knew when I put on my shoes, I was going out. Then he pirouetted and whined and begged shamelessly for me to take him, a whimper that spoke of the darkest sorrow. Worked every time.

Dante and Chamaco, my old-timers, were the only ones allowed to go with me on my daily walks into San Miguel’s center, throwing themselves on the cool Mexican tiles under the bank manager’s desk after the long walk in the heat, or waiting with me at the bakery door while I shouted my order to the cashier. Even with the gimp leg, Chamaco descended the steep hill into town and climbed up again without complaint. Polite, sociable to humans, he was tolerant of other dogs if female.

I don’t know why, but Chamaco was a sucker for foreign chicks, especially French poodles. His last crush was with a too-young Minature Pinscher he met at an art gallery window on Hernandez Macias. Lucky for him, she was into older guys. It was an innocent affair, just a bit of nuzzling through the filigreed window gate, Chamaco’s tail trembling like a cobra. Sweet to watch and heartbreaking in retrospect.

Once I was installed into my new house, December 2015, Chamaco started to die poco a poco, so I wouldn’t notice. The renal failure he’d fought for two years finally won. We were expecting el viejito Dante to go first, not Chamaco. The “Monkey” had been sick for so long we forgot he was sick. It was as if he’d waited for me to move and find my home before he decided his job was done.

On his last night, I woke and found him standing in the hall. He had the saddest expression. “I’m sorry, I’m doing the best I can,” he seemed to say. "Ya no puedo. I can’t anymore.”

Then I knew.

“You will never be afraid again,” I said the last time I held him.

He is remembered for many things, among them, the adroit skill of plugging caquita inside the holes of walls here in San Miguel. But above all, I will remember him for his passion. I miss him every day and only console myself because I know he is still here in my house. He has been reported seen or heard by my sixth-sense staff.

One day he will come back to me in the body of another animal. A dog again, Chamaqui? Or will you love me in another form? What would be large enough? Even the sky could not hold all the love you sent and continue to send me.

June 13, 2017

Casa Coatlicue

San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato

Mexico